No, Kareena Kapoor, Your Moniker KKK Ain’t Proper – Even in India

Is a deeply disturbing oppressive regime of violence not “our” problem because “we” were not affected by it?

Krustofsky, or Krusty the Klown, has his own comedy show in the American animated sitcom series, The Simpsons. His show is titled Krusty Komedy Klassic. In one of his acts he opens the curtain with “Hey, it’s great to be back at the Apollo Theatre,” looks back at the stage banner.

It shows the abbreviated title of the show as KKK, and Krusty blurts out, “That’s not good!” expecting audience resistance at the use of the acronym.

He is booed off stage as people throw food and objects at him.

Kareena’s ‘KKK’ and India’s Nazi Fixation

Let’s change the scene and take a quick look at a current Indian entertainment scenario – prominent Bollywood star Kareena Kapoor Khan has a new radio show on socially relevant issues calling itself “the unapologetic show.” The show is titled What Women Want and highlights pertinent issues of women’s agency and feminism in present day India. The iconic star-turned-host introduces herself as KKK, which clearly is the abbreviated version of her name. It is also the abbreviation of an American secret society called the Ku Klux Klan that has been propagating white supremacist hate since 1866.

In Kareena’s case, it may ‘pass’ and be construed as an innocuous use of the acronym. Yet, what does this cavalier ahistoricising really reflect about contexts, online spaces and the spirit of the times we live in?

It is perhaps not unknown to many that there is a paraphernalia of Hitler related items in the Indian market that casually normalises the dark associations of the name. A brand of ice cream called “Hitler” with Hitler’s face imprinted on the cones, “The Nazi Collection” bed linen, or a clothing store named “Hitler Clothing” – only a few examples among many.

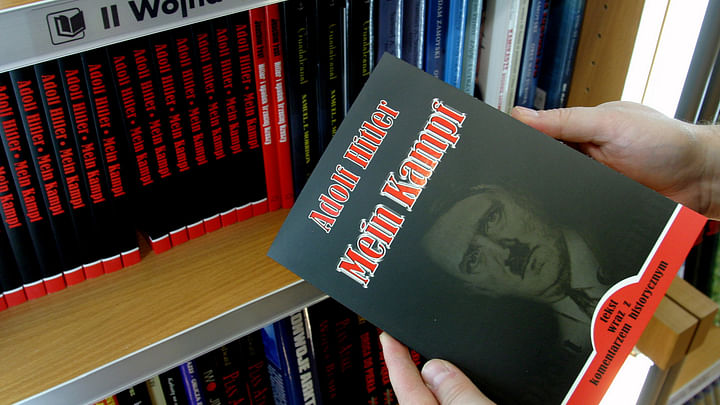

They highlight how blissfully cocooned scores of ‘us’ are when it comes to history. After all, Mein Kampf is also recorded as one of the highly read books in India. This, certainly, is a strange irony or dark parody of some kind perhaps, given that Hitler’s text doesn’t hide its fascist ideologies in any dubious metaphor.

A customer holds a copy of Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf.

(Photo: Reuters)

What’s Wrong with KKK, After All?

The Simpsons is a satiric parody of American life and it makes deeper sense in an American context, and one can also note that the backdrop of Krusty’s show in the famous Apollo Theatre in Harlem, New York. What Women Want is an Indian a semi-radio web show that caters to a certain online savvy section of the Indian population, clearly not inhabiting the same public space as the previous one.

Krusty in The Simpsons drives a significant point in that opening fiasco – that perhaps, when using the acronym KKK there is a certain framing and sensitivity that is needed, especially in platforms that reach a wide, varied backdrop of people across boundaries, watching from any part of the world.

Now, the question is how certain historically problematic terms, concepts and figures get framed, contextualised and whether they have the same currency outside of its immediate historical space and place.

Founded in 1866, KKK has had a horrific history of terror and violence in the US harkening back to memories of slavery.

In our recent memories too, the memory of violence and death in Charlottesville, Virginia, has not faded into oblivion and marks a scarring moment in our present. We, Indians, are also aware of the reality of KKK members clashing with protestors in a white supremacist rally that surfaced Nazi flags and slogans in the summer of 2017 in America. As the world watched in horror, media worldwide covered the incident, including almost every news media in India.

Why Should ‘We’ Care if ‘We’ Aren’t Affected?

So why does all this matter if it’s not really a part of “our” history? It does because we exist in an increasingly global world in which news and information (or lack thereof) reaches within seconds to millions of people across borders, but within the seemingly democratic space of social network. The horrors of Auschwitz or the Klan may not be a part of the Indian socio-political psyche, but India also does not exist in a historical vacuum.

Is a deeply disturbing historically – and resurfacing – oppressive regime of violence not “our” problem because “we” were not affected by it?

Are we, perhaps, making a big deal of an acronym or a name here, when for the larger Indian socio-politico-cultural memory, it makes no clear association?

Or, do we throw away the term in the trash-bin of History because it is irrelevant for us, when one is also reminded that India has yet to rid itself of the evils of colourism, casteism, and marginalised discrimination in varied structures of society? Particularly, India’s current entanglements with far-right politics and the increasingly divisive politics has even witnessed lynching and violence against the marginalised that has daily come to shape the nation’s realities in the present times.

No, It’s Not Being ‘Too Politically Correct’

In such a moment when identity is the keyword, and shapes dynamics of survival and solidarity, framing and language matter. Perhaps even more when it comes from famous figures who have a certain platform and are heard and followed transnationally. Maybe, finding an alternate subversive frame to reclaim a term/concept, could in some cases ease some scars of the old and what it evokes. Yet, without that kind of alternate framing, it all boils down to the problem of trivialising history, making it a farce. And that’s how events that beget trauma get normalised around us: because they are not “our” histories.

A term/acronym could be deemed harmless beyond its relevant spaces and places, and raises the question whether we are simply being “too politically correct”. It, however, also begs us to rethink of our own empathetic ethico-social roles we play in our daily lives for people who may have been affected, if not us.

(Amrita Ghosh is a postdoctoral researcher at the Center of Concurrences in Colonial and Postcolonial Studies, Linnaeus University, Sweden. She has a Ph.D in Postcolonial Literature and Partition Studies from USA, and has been a lecturer at Seton Hall University, New Jersey.)

(At The Quint, we are answerable only to our audience. Play an active role in shaping our journalism by becoming a member. Because the truth is worth it.)

News

Netizens React with Shock to Abhishek Bachchan’s Alleged Second Wife Seen Hand in Hand with Him!

Title: Abhishek Bachchan Seen Hand in Hand with a Second Wife? Rumors Explode and Netizens React Recently, a photo of…

Abhishek Bachchan Appears at the Airport with the Bachchan Family, Fans Ask: Where Are Aishwarya and Aaradhya? The Breakup Seems All but Confirmed!

Abhishek Bachchan, Shweta Bachchan Nanda and Jaya Bachchan spotted at Mumbai airport, fans miss Aishwarya Rai Bachchan and Aaradhya Abhishek…

Abhishek Bachchan Avoids Paparazzi with Jaya and Shweta; Aishwarya Rai’s Absence Sparks Public Uproar Over Family Rift!

Abhishek Bachchan Dodges Paps with Jaya and Shweta; Fans Miss Aishwarya Rai, Call Family ‘Incomplete’ Abhishek Bachchan seen with his…

Shweta Bachchan’s “pout” shows contempt, and netizens are reacting strongly!

Shweta Bachchan Is Shocked As Son, Agastya Shares His Views On Toxicity And Chivalry, Netizens React In a video doing…

Amitabh Bachchan broke his promise to Aishwarya Rai, and after continuous family disputes and divorce scandals, that is also the reason she left the Bachchan family with her daughter.

Amitabh Bachchan Promised A College In ‘Bahu’ Aishwarya’s Name In Daulatpur, Later Left It Abandoned Once, Amitabh Bachchan and his…

Amitabh Bachchan’s Omission of Aishwarya Rai’s Name Sparks Netizens’ Reactions

Amitabh Bachchan Recalls Performing On ‘Kajra Re’, Skips Mentioning Aishwarya Rai Amid Family Feud As Amitabh Bachchan walked down memory…

End of content

No more pages to load

Leave a Reply